August 4, 2022

Obstacles and Strategies in Research Data Sharing and Reuse

By Jennifer GibsonAs a follow on to our Building Data Resilience through Collaborative Networks Symposium, we are publishing a blog series featuring each of our presenters. This is the second in that series.

I’d like to start my remarks by talking about our end game: achieving the full power for the open sharing and reuse of research data, some of the big obstacles in front of us, and how I feel we might overcome them. Given the group assembled here I’m optimistic about how we might work across our network and push through.

Achieving the full power of open data sharing and reuse is dependent on changing behaviour among researchers. And that’s something I’ve worked on together with many of you in different ways, through my work at SPARC (a very long time ago), eLife (for my most recent ten years), and now Dryad (where I joined last October).

With these organizations we’ve tried changing behaviour through:

- Funder and institutional policies to nudge if not require change

- Service provision to support and enable change

- Education about the reasons and possibilities for change

- And competition – with attractive and competing offerings to encourage researchers to divert from their usual paths

I’ll focus on this last one for a moment.

A short case study in change

I wonder if we might agree that research assessment practices remain a bastion for the status quo: so long as researchers continue to only recognise publication in specific journals as the marker of achievement, the impact of everything else we do is limited. (I should note that my own perspective is heavily influenced by biology because of my work at eLife in particular). What I learned at eLife is that there is a way to win that game – just not the way I’d thought we might win it. I’d like to talk about that for a minute.

In case you’re not aware, eLife is an open-access journal – yes – and a non-profit organization started in partnership by three of the most prestigious and wealthy biomedical research funders in the world: the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in the U.S.; the Wellcome Trust in the U.K.; and the Max Planck Society in Germany. The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation were a later addition. The initiative was very, very well funded, with 18 million pounds for its first 5 years to drive change, to be an instrument on behalf of the funders to transform science publishing and challenge those proxies, the status quo in research assessment, and to put the publishing process back in the interests of science.

Having been founded by these very prestigious funders. The next move was to recruit 196 of the world’s most preeminent scientists to serve as working editors.

Here’s what I got wrong: I thought that, having the backing of these three organizations, and these very accomplished individuals would pave the way for competing for the top papers. I thought: if anyone could compete with the top journals and the impact factor, it would be eLife, and I would see to it.

However, the skepticism among our colleagues in research runs deep, and while I was talking about eLife I encountered a number of arguments. From postdocs I heard: I’ll do it when my PI (principal investigator) does.

I want to suggest that this is a microcosm for behavior change, publishing in this one new journal, and the postdoc response is that they need to see proof of change among leaders first. Similarly, the post-doc wants to know: is it going to get me a job – because the publication record is, as you know, the driver of advancement in science.

The PI’s arguments were, in the main: are my colleagues going to see it, is the audience there for the research I’m publishing, and; I can’t go against my post-doc.

I found them really difficult to move, and difficult to argue with when, for a postdoc, it can be a matter of providing for a young family. The risk of going against the status quo is too much to bear.

But. We did it. In the first ten years of eLife, we built a destination for research in neuroscience, cell biology, and 17 other disciplines across biology and medicine. We became a “third leg in the stool” (referring to the big three journals in biology) in structural biology, and I know we were cited on funding applications and got people jobs.

And we did it by building trust: we made a promise that every submission would be given a fair shake, and we delivered. It took time, it took convincing – mostly by our editors of their colleagues – but we did it.

By convincing individuals to embark on a new path and by delivering on the promise we made them, we began to change how people assess the quality of research.

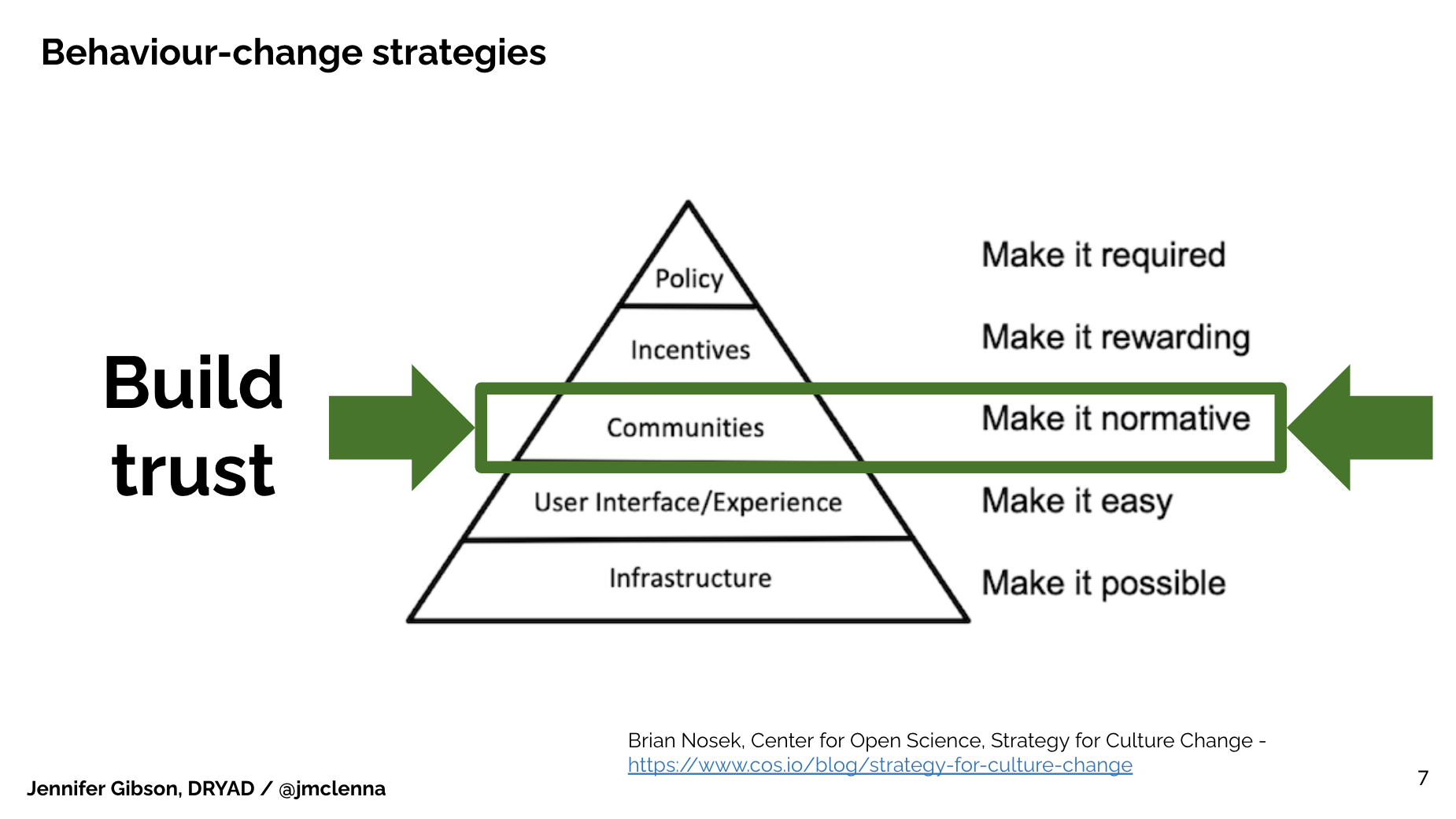

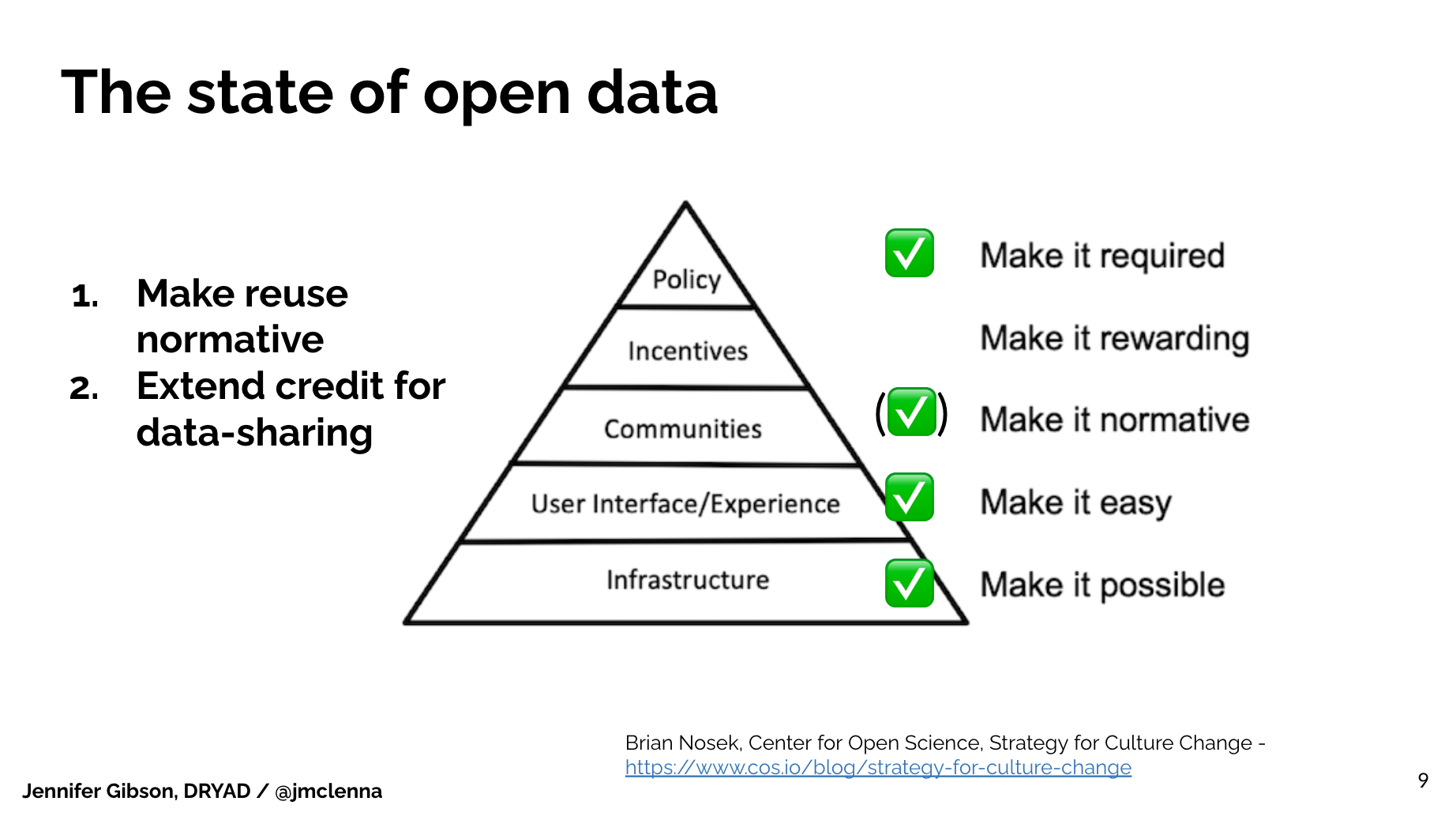

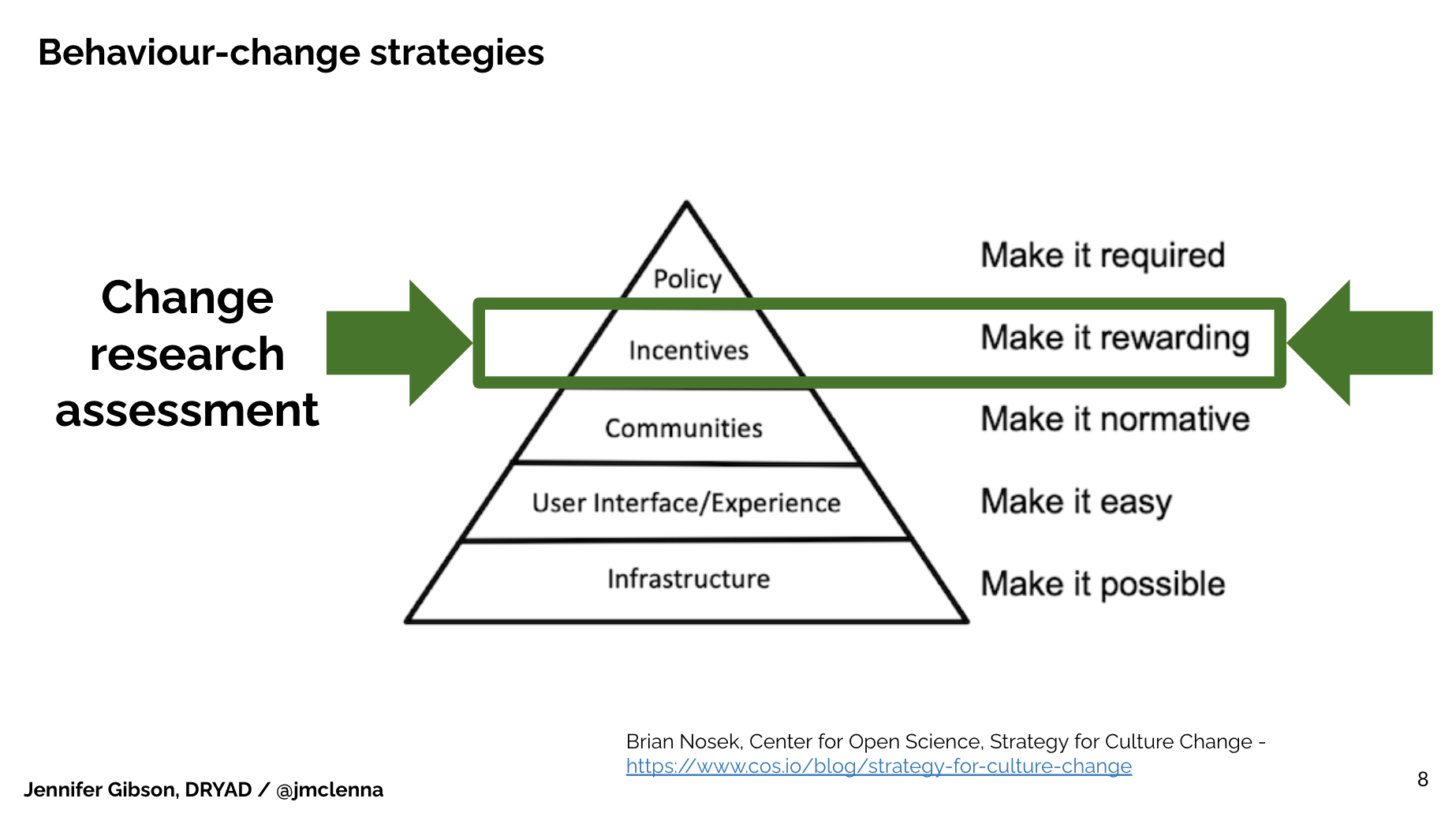

I’m going to invoke Brian Nosek’s strategy for culture change diagram here (Brian Nosek, Center for Open Science, Strategy for Culture Change. https://www.cos.io/blog/strategy-for-culture-change). It may be familiar to many of you. It outlines 5 different interventions that we can make to change behavior, to change the culture of research.

At the bottom of the diagram, he names infrastructure: We need to have the systems to make change possible. We need systems to begin, then we need it to make it easy for participants, users, researchers to engage with that system, or they’re gonna bounce and go away.

We then build communities of practice and peer groups for whom this new behavior becomes the norm. Then, there’s the incentivization process – which could be internal or external. I’ll come back to that in just a moment.

Finally, there’s of course a policy environment and making the behavior required.

What I’d like to suggest here, in applying Brian’s framework to my experience at eLife, is that a community of individuals who adopt the intended change in behavior at the same time change their incentives environment. Individuals winning over other individuals grow a culture for recognising a new behavior that they value. The pathway to change begins with moving a few people to do something different.

Obstacles to change in research data

Turning now to research data, where I’m still new, I feel I see a very powerful combination of systems, policies and practice – an engine ready to drive us forward, toward achieving the full potential for interacting with research objects such as data and code in the open, in the computationally robust environment we have available to us.

What seems to still be in front of us is getting researchers to interact with open and reusable data, such that they incorporate it in their own work, value and acknowledge the original authors, and begin to credit one another for assembling, packaging and sharing data.

There are a lot of lessons from publishing that I hope to bring to bear in extending the audience for Dryad – the foremost among them being to bring an audience to the data.

I’m particularly optimistic about the use of cloud computing, and deploying code and data in a live, reader-friendly environment, such that the reader can interact with the data, maybe see something different, and incorporate it more effectively into their own work. eLife’s Executable Research Article (https://elifesciences.org/collections/d72819a9/executable-research-articles) and the Reproducible Preprint offered by NeuroLibre (https://www.neurolibre.org/) are two efforts I know of that offer the chance to edit the code underlying a visualization of data in situ – within the body of the research article.

It’s especially powerful to offer this experience within the body of the research article because it’s a familiar place to the reader-researcher. They already have the habit of going to read the latest findings – and there’s the data and right there, in the front seat, in a way that it can be touched and interacted with, potentially opening up new avenues of investigation right there. I’m hopeful that this type of initiative will help close the gap between researchers, reuse of data, and recognising sharing and reuse behaviors.

Leveraging the collaborative network

Having reflected on my ambitions for research data, closing the gap in research assessment and helping researchers to value data sharing and reuse – which is key to achieving the benefits of open data for research, science and society, I find myself asking if we have everything we need to achieve our ambitions?

And I suppose we don’t. While Dryad has a lot of data, a great connection with Zenodo for software, and an attractive destination page for published data and related objects, we don’t have the facility for cloud computing.

Nor, perhaps, should we. In the interests of the collaborative network, I wonder how we might deliver our data and connected software to other end points where there might already exist both the talent to build cloud compute environments and an audience ready to use them. A synthetic biology unit for example within a research institution is no doubt already leveraging their computational power to interrogate local data in more ways. How might we draw that talent out from inside those walls? Are the institutional collaborations I’ve described here a pathway toward that? And what would publishing organizations do if they were able to offer cloud computing technology to their readers?

I can see a future here, but I’ll leave the rest to your imaginations.